The Roots of Epic

Why the term "performance"? The word is appropriate in more than one way. On the one hand, The Plains of Abraham is like one-man theatre, with the rhapsode (epic performer) impersonating various characters and speaking for them in the first person. So "performance" fits there. On the other hand, about half of the poem is direct narrative, with the rhapsode describing events as they unfold. Here it is the past itself which is reactivated, brought back (briefly) from oblivion; history becomes the act of the performer. So "performance" also suits the deed of commemoration.

Equipment

Initially, I performed without a rhabdos, for example on Rhapsodic Tour 2000. As with many components of the poem, however, the subsequent inclusion of a rhabdos was not a nostalgic revival of an ancient practice for its own sake. Rather, as I grew more experienced, I became aware that gesturing with both hands looked and felt too histrionic. What to do? Obviously I couldn't keep a hand in one pocket, or hitched to my belt, for an hour. So I brought in the rhabdos, ideal for securing one hand while the other is gesturing and also handy as a prop.

Gesture

Scope and Structure

This telescoping of events into a single grand climactic episode results from the need to cater to audience interests: as the poem was evolving, I found that episodes not directly connected to Montcalm and Wolfe had a weak grip on the audience, so the main characters have become the vehicles for material from the wider history, and what was originally just the central episode (of six), the Battle of the Plains of Abraham itself, has taken the rest of the material into its orbit.

Diction and Formulaic Language

The archaism arises from occasional inversions of word-order ("then to the ships he came" instead of "then he came to the ships"), usually for metrical reasons, and from the occasional use of a non-colloquial word ("slain" instead of "killed," for instance). This latter type of archaism is meant to remove the action of the poem from our usual world; interestingly, audiences have sometimes asked if The Plains of Abraham is some "rediscovered" text contemporary with the events it describes! In fact, the language of the poem is far more direct than the ordinary (let alone poetic) speech of the 18th century, or even of the modern day: often an older word or phrase is used where we would tend to use some polysyllabic neologism.

Formerly, scholars were inclined to write off formulaic verse as "the best the poet could do" given his illiteracy, or to ascribe the preservation of formulas to the conservatism of the Dark Ages. But formulas were not mindless stopgaps. Rather, from the point of view of composition, the recombination of formulas in tale-telling was the epic poet's craft, appreciated as such, and thus conservative in effect rather than in purpose; while from the point of view of the audience, the deployment of hefty formulas allowed the listener's imagination to assimilate new information at a manageable rate instead of being overwhelmed by complex, compact detail.

English poetry has not been formulaic since the days of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, that is for more than six hundred years; so The Plains of Abraham is obliged to create its own formulas. Skilful recombination of formulas is thus not an appreciable characteristic of the composition, except insofar as the audience comes to recognise repetitions ("upon the Plains of Abraham," "before impregnable Quebec," etc.) as a performance unfolds. But the second, audience-oriented aspect of the formula remains vital: thanks to the heftiness of these set phrases, the poem never leaves the listening ear behind. And there is a third benefit: for me as for ancient oral poets, formulaic phrases in The Plains of Abraham allow for improvisation in performance - a useful tool if memory falters.

Rhythm and Meter

Though I have not myself experienced the poem as a listener, audience members have frequently commented that the experience of listening to the poem, with its regular meter, is one of mild hypnosis. This effect should not be confused with "putting an audience to sleep"! Rather, if the ear is guided along established cadences, boredom, the result of exhaustion, is counteracted; though the audience may psychologically rebel against regular meter for the first five minutes or so, soon the listening ear accepts the framework and enters inside the rhythm - an experience familiar to anyone who has seen a good Shakespeare performance. As reported by listeners, time seems to stand still.

The meter itself is an innovative one, however. The classic meter of English verse is iambic pentameter — used in my new epic poem, The Odyssey of Star Wars — whereas The Plains of Abraham uses iambic octameter, a significantly longer line. The choice of octameter was inspired by the Greek and Sanskrit epic meters, hexameter and anustubh.

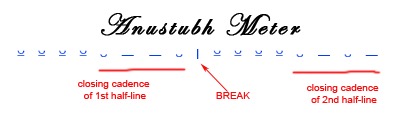

Anustubh meter consists of a sixteen-syllable line, broken into two eight-syllable half-lines by a break in the middle of the line (a "medial caesura"). Like ancient Greek, Sanskrit builds its verse from patterns of long and short syllables. (Most modern European languages, including English, no longer distinguish long and short syllables, classifying them instead as accented or unaccented). The pattern of long and short syllables in the anustubh meter is as follows:

Here we see the break in the middle of the line, as well as the fact that the first half-line and the second-half line have different closing cadences (short-long-long-short for the first half-line, short-long-short-long for the second half-line). The difference between these closing cadences has an important effect: the audience is never left unsure of whether they are hearing the first half-line or the second half-line, even though both halves have the same number of syllables (eight).

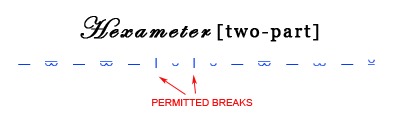

The dactylic hexameter of Greek epic features a similar patterning of long and short syllables. The most common type of hexameter is the "two-part" type, with a single break in the middle of the verse (permitted in one of two places). This break divides this type of hexameter, like the anustubh, into two balanced halves:

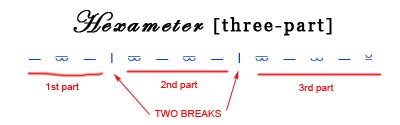

In addition to the two-part type, however, there is also a three-part hexameter. In this type there are two breaks, dividing the line into three parts:

It is against this background of the hexameter and anustubh that The Plains of Abraham builds its meter in English.

The first question was: what rhythm should be used? Here the rhythm pretty much had to be iambic, that is, a series of iambic feet, since this is the basic rhythm of 90% of English poetry and speech. (An iambic foot consists of two syllables, the first unstressed and the second stressed. To facilitate comparison with the ancient meters above, a stressed syllable is here indicated as a "long" syllable and an unstressed syllable as a "short" syllable.)

Once the iambic rhythm was settled on, the next question was: how long should the line be? The great iambic meter in English is iambic pentameter, used by nearly everyone from Chaucer to Tennyson, and famous in the epic genre as the meter of Milton. But iambic pentameter is a much shorter meter than either the hexameter or the anustubh meter; inevitably, one half of every line of iambic pentameter does little more than "set up" the second half, and balance is accordingly achieved either through the use of couplets or through enjambment (the running of a sentence from one line to the next). These were two effects to be avoided, since internal balance is very important to a line of epic verse, simplifying narrative and keeping the pace of description steady over the long haul; while enjambment, if too prolific, forces the audience to concentrate too closely. In order to achieve the marvelous degree of internal balance displayed by the hexameter and the anustubh, it was necessary to find a meter of similar weight, capable of division without provoking continuous enjambment.

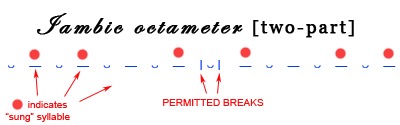

The result, developed with the help of my brother, David Mitchell, in January of 2000, was iambic octameter, or a sixteen-syllable line in iambic rhythm (alternating unstressed and stressed syllables). This is exactly the number of syllables in the anustubh meter, though without the short-long-long-short closing cadence of the first half-line (difficult to achieve in English). As with the anustubh, a break follows the eighth syllable; like the two-part hexameter, however, the break may come one syllable later, after the ninth (unstressed) syllable.

The removal of the distinctive closing of the first half-line characteristic of the anustubh (which, as we have seen above, serves to distinguish the first half-line from the second) had a serious flaw, however: audiences were prone to confusing the first half-line with the second-half line, both usually of eight syllables and now undistinguished from one another. The solution was, first, the introduction of "song tones," a quasi-chanting of certain syllables in the line (in 2001): by "singing" the first, second, and fourth stressed syllables of the first half-line while "singing" the first, third, and fourth stressed syllables of the second half-line, the performer was now able to distinguish for the audience the first and second halves of the verse. These were eventually reduced to simply clearer and more emphatic pronunciation of those syllables, so that the structural role of the syllables persisted but the oddness of singing them was dropped.

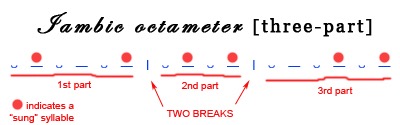

For additional variety, in addition to this two-part line, a three-part line was now introduced (in the winter of 2001, following the first Rhapsodic Tour). In keeping with the three-part division of some hexameters (described above), the iambic octameter line could now be broken into three parts:

(Note how the position of the marked [formerly "sung"] syllables also varies in this three-part format.) The three-part octameter began to be interspersed among the two-part lines, allowing for controlled rhythmic variety amid the larger poem and incidentally reminding the audience (aurally) that it takes sixteen syllables to make a line.

That is where the meter currently is: iambic octameter, in all its glory!

Speech and Story

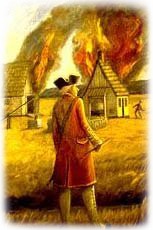

In addition to narration and speeches, there is a third category: the similes. The mini-genre of these epic similes is borrowed directly from Homer; they are used as pacing devices, deployed to separate narrative episodes. They are drawn from nature, and relate incidents in the poem to the natural phenomena of the Canadian landscape. In a full performance of the poem, there are thirteen similes, each one pertaining to a different province or territory: mountain streams for BC; the Chinook for AB; prairie sunset for SK; Red River floods for MB; storm on Lake Superior for ON; ice storm for QC; Reversing Falls at St. John for NB; a dismasted frigate for NS; dewy grass for PEI; breakers for NL; mountain flowers for YT; a wolf pack for NT; a polar bear killing a seal for NU.

One point: in the telling of the story, care has been taken that the events described never contradict the historical record. In contrast to the ancient epics, where the gods interact with the human characters and interfere in the story, supernatural events have been greatly restricted; even when they do occur, they can be taken as the interpretation by contemporaries of natural events (as when the rain before the Battle of the Plains of Abraham is described as the Virgin's tears in heaven). The result of such a strictly historical emphasis is that audiences are apt to take the poem as literally true, at least for the duration of the performance while they are under the spell of regular meter.